JILL PAZ AND HER COCONUT GROVE PAINTINGS

In this show entitled 'Echo of a Site', Paz presents a new series of paintings using Palm Tree imagery.“I hate palm trees” or “Palms are not beautiful; possibly they are not even trees.” 1 So literary theorist Elaine Scarry tells us in her book 'On Beauty and Being Just'.She is not the only one who has problems with palms. Palm trees, coconut trees are so common here that they become almost invisible. We see them every day. But to someone brought up in the UK like myself, or in Canada like Jill Paz they remain an archetypal signifier of the exotic. An advertising jingle from the Sixties still rings in my head “Lilt, Tropical Lilt.” And instantly I have an image in my head of palm trees especially coconut trees, Bacardi, golden beaches and tropical sun. As he was shooting his Vietnam war movie Full Metal Jacket, 2 in East London Stanley Kubrick added them as a backdrop to make it all look “tropical”. However, I I live here now and I see them in the garden. They are an everyday sight. And they are so scruffy! In a diary I wrote of how they reminded me of a woman with long hair waking in the morning. Their hair tousled and messy. Scarry’s book revolves around a discussion of Henri Matisse’s Niçois paintings – the paintings made when he spent half of each year in Nice (1921-1938), paintings filled with women, clothed and unclothed, flowers, curtains, carpets, pianos, windows – and palm trees. A calm luxurious world. Scarry’s discussion of these paintings, this languorous domestic world, is about learning that palm trees can be lovable, can be beautiful. And in the process she argues that beauty is important, that it does have some relationship to truth.Is what Paz is doing in these works similar?In more contemporary art who likes Coconut trees? That quirky, not quite a Pop artist Sigmar Polke liked them as did that even more quirky artist of the Eighties Rene Daniels. They pop up in the work of Marcel Broodthaers. Three quirky, quizzical, often comic artists. Or, think of, Rodney Graham’s 1997 video Vexation Island where a pirate wakes, finds himself lying on a desert island beneath a coconut tree, thirsty, the coconut above temptingly out of reach. After assorted shenanigans trying to get the coconut it falls and knocks him out again. He wakes… (and repeat).Paz’s work is more sober. The palm tree is not for her just a slightly ludicrous signifier for the Tropics. Her work has always been about taking old images and revivifying them, making them new again. Her transformations are discreet, subtle but effective.The photos she uses are of the palm trees or coconut groves near the old family house where she lives – a settlement around a golf course, now less smart than when first laid out – a place with something of an air of dilapidation and distressed gentility – a country club atmosphere. During the Pandemic she would often walk amongst them. She says these palm trees she lived amongst made her think of ghost stories.The photographs she took of them then are the basis for these paintings.She sketches the composition – drawing has in recent years become an important part of her process. Translated by the laser they become pixelated, degraded, or essentialised images. These she doctors further on Photoshop, using “magic wand” especially, to tidy things up, to get rid of foreground detail, etc. She has to work on small pieces or fragments because her studio is so small – but she turns this to her advantage.These multi-panel works remind me of one of the transitional phases in Piet Mondrian’s progression from figuration to abstraction – those paintings made in 1917 of colour squares jostllng for position on the canvas. He was responding to how Bart van Leck had been placing colour squares on a wall. 3 Paz’s paintings though have none of the idealism of Mondrian or Van Leck.Everything is provisional here. As always, these images of Paz are so very in between. It is an unstable grid, but calm, the squares jostle with hesitation, not with anger. They are reticent works, as are Matisse’s Niçois paintings, her palm trees are frozen in motion, all stilled, just as, for all the pianos and guitars he includes, Matisse’s domestic scenes remain mute. Her colouring is intuitive – she has been affected and made more comfortable with colour by a break in the USA making and glazing ceramics. She applies it with an air brush. She likes the delicacy of that process. These works are of their time, the lockdown, when the restaurants and fast-food joints disappeared and the kitchen table became the centre of many people’s universe. We become more aware of what Norman Bryson in his influential book Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting (1990) calls “feminine space”. We could call these works “intimate” or “homely,”or “kitchen paintings”.How does this intimacy reveal itself? Her working process, using a laser to burn a digital image on to a surface, may seem analytical, impersonal, unemotional. Her subsequent application of paint leaves no trace of gesture, shows no personal “handwriting”. She has talked of making these works with the “cool air of detachment evident in the self-effacing processes of Minimalism.” But yet the paintings seem plaintive to the sensitive viewer.And things look different. She is making palm trees new again. Making them visible, and, possibly, beautiful.As Scarry points out from Homer onwards beauty is the unprecedented, the unexpected, the new. 4 Something that is either life affirming (Matisse’s Niçois paintings) or life challenging (Rilke’s demand at the end of one poem: “You must change your life” 5 )“Matisse,” Scarry writes, “never wanted to save lives. But he repeatedly said that he wanted to make paintings so serenely beautiful that when one came upon them, suddenly all problems would subside.” 6 Paz’s paintings belong to a different, more shifting and inconstant age. They are about being comfortable, as she says, with palm trees, but her propositions are, unlike Matisse’s, always provisional – between suggestion and statement. If Matisse’s Nicois paintings are about beauty, are beautiful, her Cavite paintings could be about beauty, could be beautiful.However provisional or in-between they may seem these works are elegant, thoughtful have a presence and are strangely beguiling.- Tony Godfrey 20231 Elaine Scarry, On Beauty and being just, Duckworth, 2000, p.19. Elaine Scarry is best known for her 1985 book The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World.

2 Kubrick was shot the film in East London, in the abandoned Beckton Gas Works. He imported 120 or more palm trees from Spain to make it look tropical. Planted and abandoned in containers most of them died.

3 See Hans Janssen, Piet Mondrian, a Life, Ridinghouse, 2022, pp310-312. These wall works of Von Leck’s could be seen as a forerunner of Installation Art. Mondrian subsequently began to turn his studios in art works in their own right by placing squares of monochrome colour on the walls. (See Cees W. de Jong, Piet Mondrian: the studios, Thames & Hudson. 2015)

4 Op. Cit. p. 23

5 Archaic Torso of Apollo, 1908.

6 Op. Cit. p.33

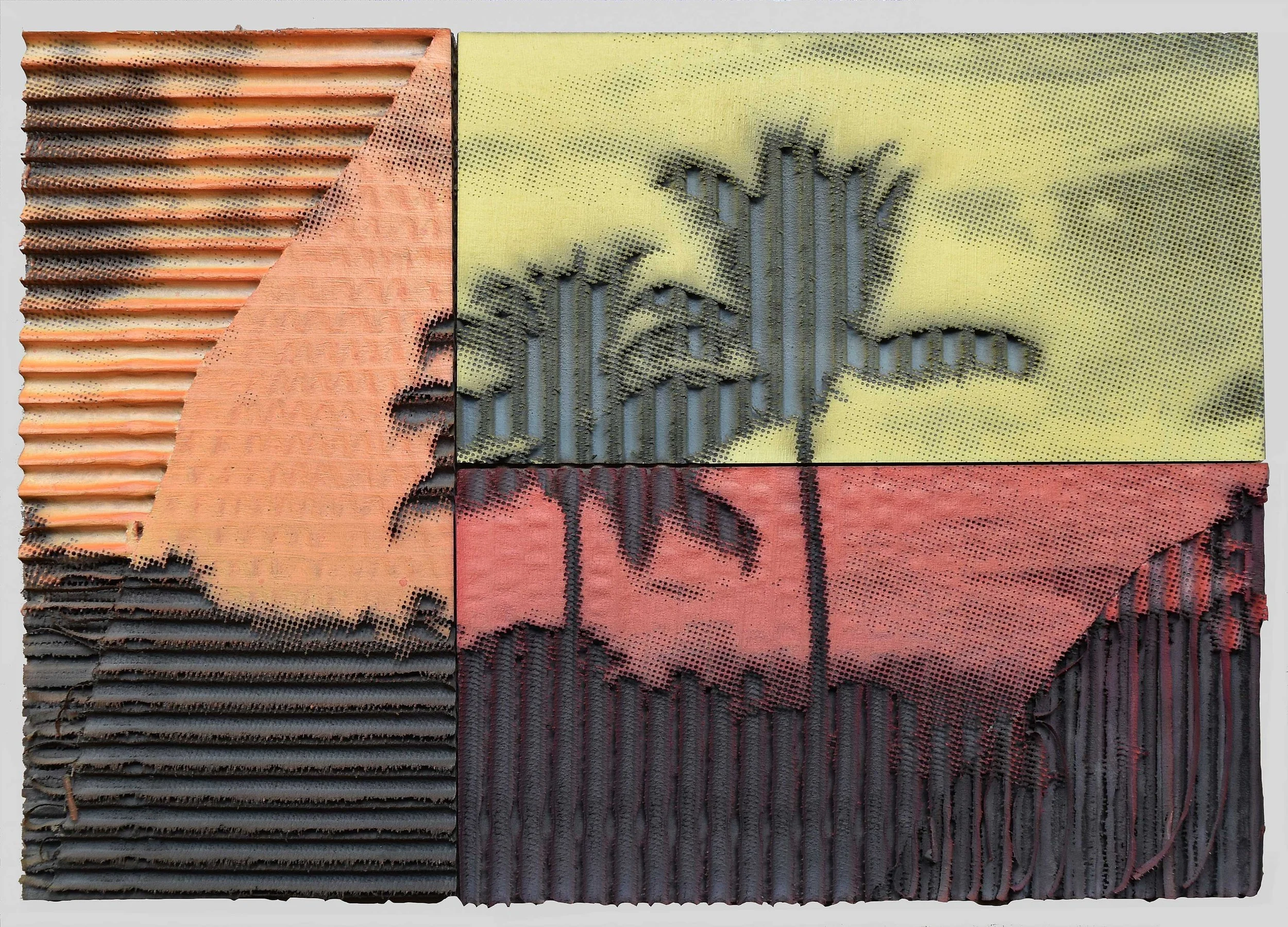

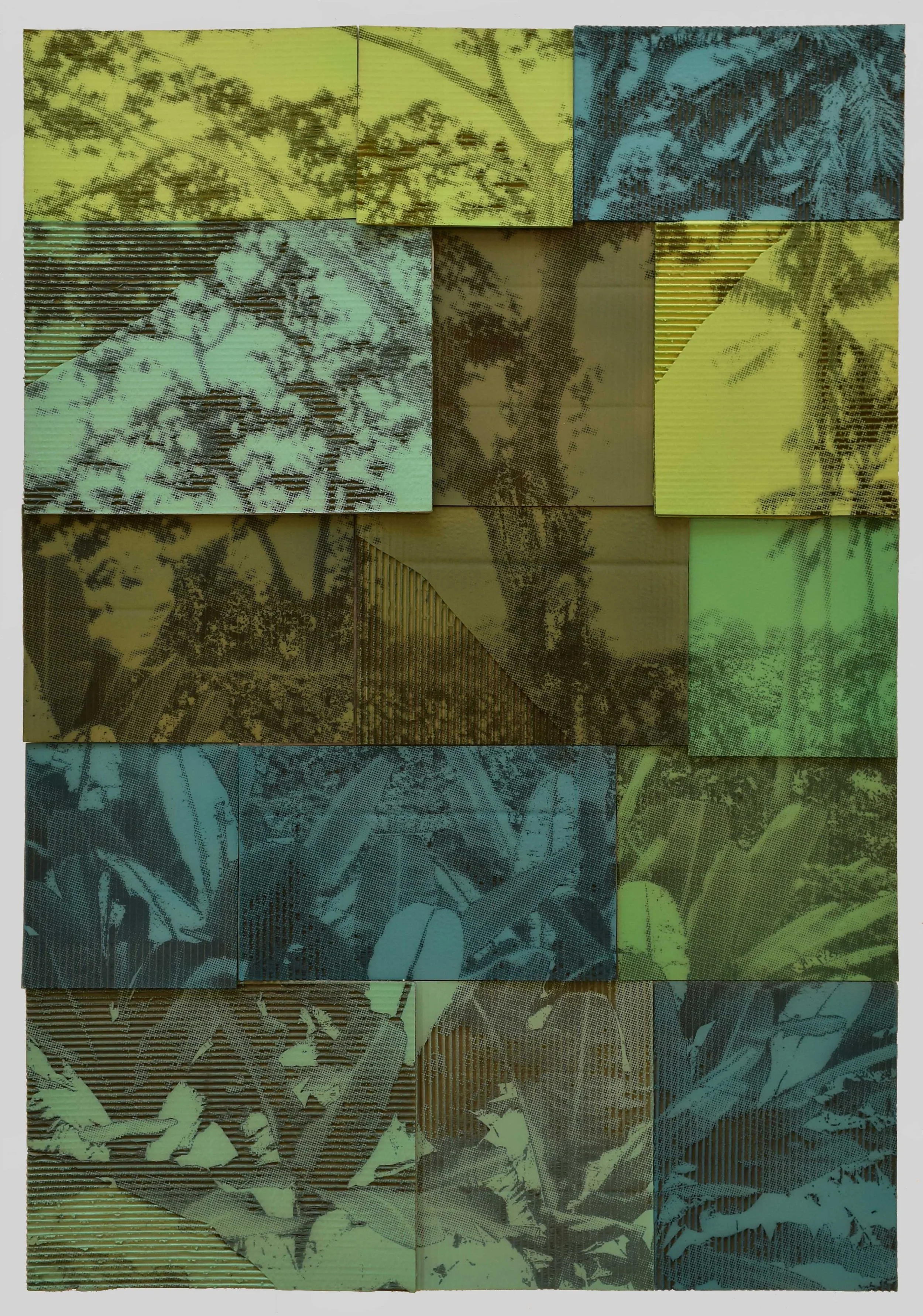

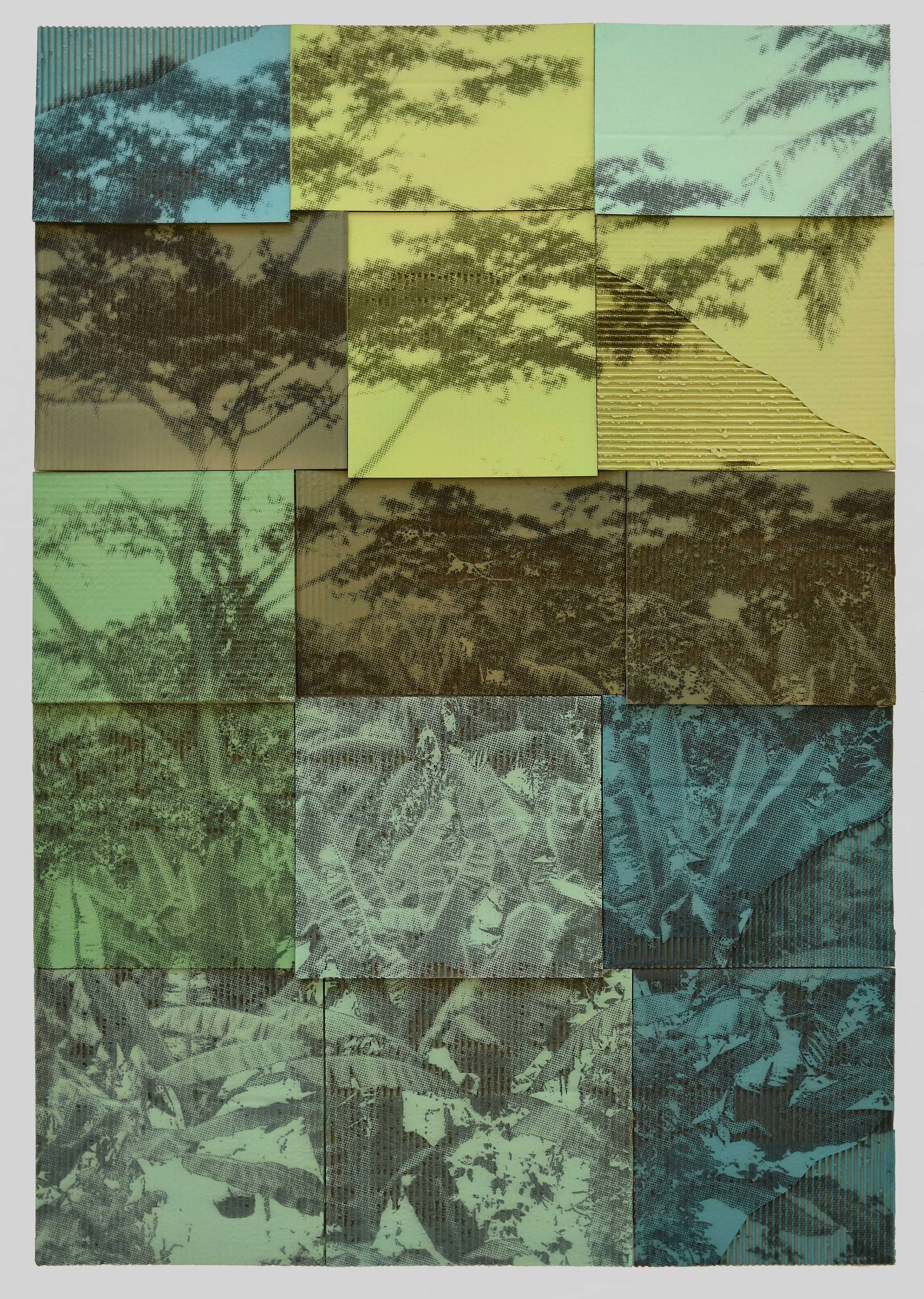

Left to Right: 'Acacia', 2022, Acrylic on laser-carved cardboard, 93.2 x 134.6 cm (53 x 37 inches), 'Coconut Tree', 2022, Acrylic on laser-carved cardboard, 93.2 x 134.6 cm (53 x 37 inches), 'Palms', 2022, Acrylic on laser-carved cardboard, 93.2 x 134.6 cm (53 x 37 inches)

Jill Paz, Sunset Jungle, 2022, Acrylic on laser-carved cardboard, 127 x 85 cm (33.5 x 50 inches)

Palm trees have an allure of a tropical vacation. The tree itself towers high above our heads, its single trunk rises to a crown of fanlike leaves, each blade radiating into an elegantly speared tip. Growing up in North America, I would associate the palm tree with luxury and also of an Imperialist bygone era. Although the image of a palm tree is depicted often on home and personal objects, from dresses and wallpaper, they can be a livelihood for entire communities in the tropics.

Since moving to Manila 6 years ago, I have this sense of trying to understand where I am from. My relationship to my studio space has helped me through this time of change and upheaval. At the height of the pandemic, in the midst of months long lockdowns, the palm trees outside my studio window provided solace and an anchor to the isolation. When I was able to visit my studio outside of the city, I would photograph the palm trees I encountered on my walks.

The first painting I made in the series was at the same time that Taal volcano erupted in 2020, blanketing my studio space in Silang Cavite with a layer of grey dust. The make-up of the painting, of burnt substrate and dust, captures the feel of the landscape, as the volcanic ash made the landscape a muted monochrome. The natural event felt like a foreboding precursor of what was to come. I kept this painting tacked onto my wall for 2 years, until I started to color my cardboard works last year. Using a technique of laser-carving onto layers of cardboard and air-brushing vivid colours onto the burned incised substrate, my compositions explore a tactile process that is both methodical and intuitive.

The title of the series ‘Echo of a Site’ refers to reflecting on one’s environment. Drawing from photographs and my own recollections of spaces I am familiar with, my new series of paintings reveal an analytical, yet deeply personal re-imagining of my environment. There are repetitions of a specific landscape, and horizontal or vertical patterns of the substrate repeated and carried on from one painting to the next. The laser machine which itself is a technology of precision used for creating multiples, is used here as a medium to create a single work of art, its precision subverted to create glitches and mess-ups that create the faintest and delicate carved lines.

-Jill Paz, Quezon City, Metro Manila

10 February 2023